01 03

18 04

2014

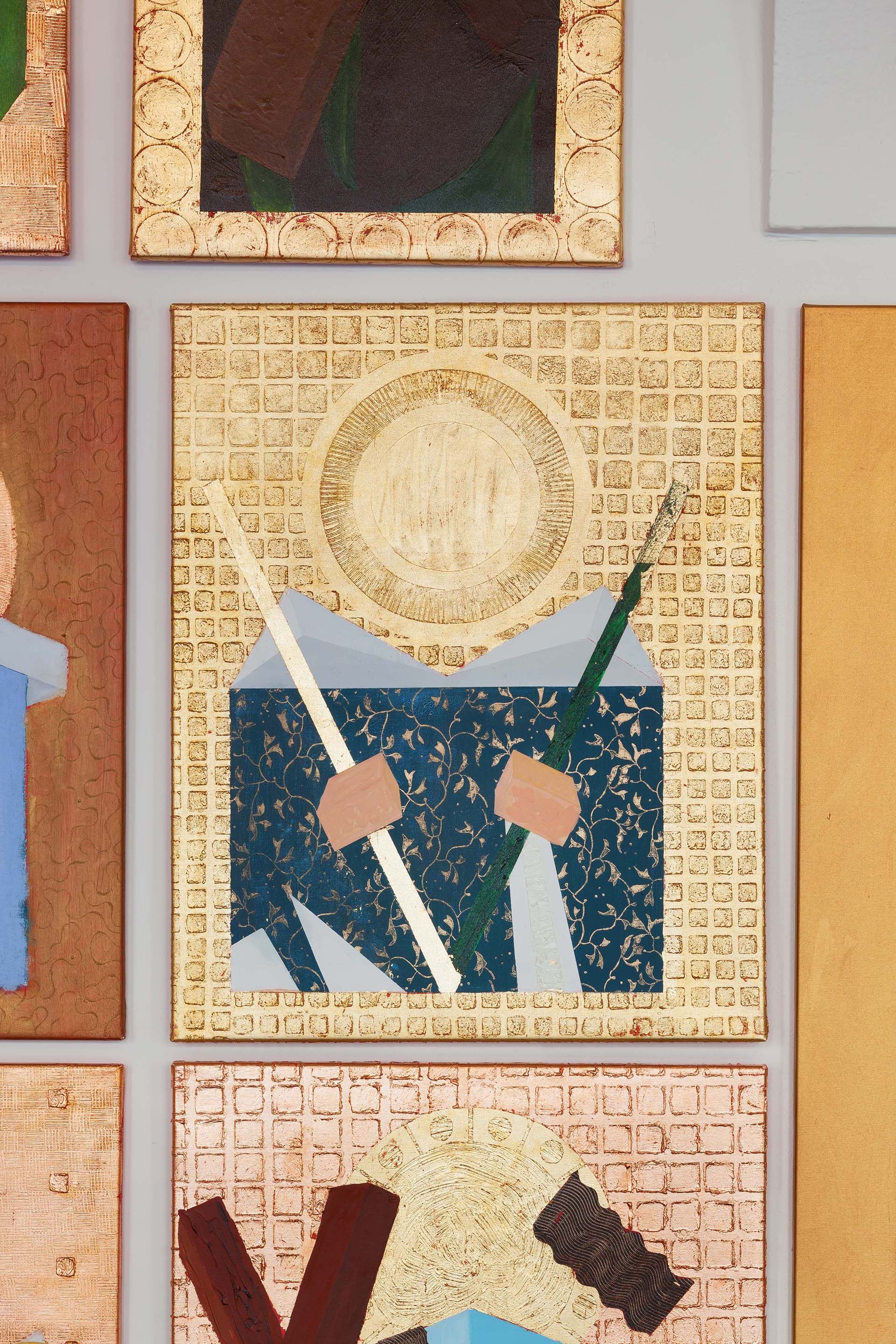

The Golden Geometry

Luděk Rathouský

Curated by Jana Bernartová, Jen Kratochvil

In the history of art, the Middle Ages era occupies a very specifically dominant position. In any part of the world, the masterpieces of the lofty Gothic invoke both spiritual and aesthetic captivation throughout the social spectrum. It simply does not matter whether the viewer is a scholar, official, serviceman or worker, since for each one of them, a view up to the vaulted ceilings of cathedrals offers a certain kind of emotion. According to the statistics of the National Gallery, the local museum scene shows that it is the exhibition of the Medieval Art in Bohemia and Central Europe at the Convent of St Agnes of Bohemia that is the most popular permanent exhibition, while the collection of modern and contemporary art at the Veletržní Palace is completely empty.

Despite being so frequently labelled as the Dark Age in the past (which is the myth disproved not only by Umberto Eco and The Name of the Rose), what makes the Middle Ages so attractive?

While simplifying to a large extent, i would take the liberty to mention one of the possible answers. The Gothic art is extremely distant to us, not only in the perspective of the development of visual art, but mainly in the perspective of the human development and the shift in the perception of spirituality and aesthetics. Apart from professional medievalists, the scholars of the Middle Ages, we are often able to see (I dare not say understand) merely the visual surface of the semantically stratified masterpieces. The concept of the “period eye” of the art historian Michael Baxandall from the late 1980s explains the changes in the human perception on the basis of the contemporary context. In short, we cannot perceive the Gothic scenes in the full content of their origins, since we do not live in the Gothic era.

What does this imply to us? What do we lose, what are we deprived of and what do we deprive of voluntarily? Compared to the highly intellectual demands imposed on the human by the art ranging from the first avant-gardes of the beginning of the 20th century up to contemporary art, the Gothic visual expressions have been reduced into the position of glossy and glittery facades, being ultimate casualties of the mass tourist industry.

A classical painter from the visual perspective, LuděkRathouský, the Head of Department of Painting at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Brno University of Technology, and the member of the “Rafani” art group, has been subjecting the Gothic painting (or rather its perception) to intense critical assessment or a number of years. At first, he worked with the cycles of the famous medieval masters of VyššíBrod, Křivoklát, and Litoměřice. His new series refers to the work of the afore-mentioned Theodoric of Prague, whose cycle of 129 panel paintings (out of 130 originally) grants a spectacular character to the Chapel of the Holy Cross at the Big Tower of Karlštejn Castle.

Rathouský creates the cycle again, in the full number of the preserved paintings, this time, however, not as a masterpiece in which each component has a substantial value, but rather as a critical reflection of the succinctness of perception, reluctance of context-based thinking, as well as the commodification of the contemporary art. He does not transfer the figural scenes well known from the Castle onto his canvases. In fact, he deconstructs them on the basis of the first reading of colour surfaces and blurring visual impression up to the pure geometry. It is the surfaces that remain, yet without any content. What remains is a mere residue of the grandiloquent and pompous mediocrity emphasised by means of replicating the same principle in the whole cycle. What remains is the author’s vision of the present in which we are no longer able to see (i.e. think using the eye) but merely see succinctly and perceive hastily. Apart from its critical message, however, the power of Rathouský’s cycle consists in the technical quality of individual painting, as well. Even though he attempts to create the impression of multiplied mediocrity, demanded within the tourist industry, his painting work again reaches its peak, similarly to the earlier Gothic-reflecting cycles.

The geometric surfaces themselves carry rich Gothic ornamentation, being full of bright colours and golden decors. The author’s Theodoric is produced in various formats, ranging from literally tiny to large mural canvases. In terms of the technique, they are a unique combination of acrylic and “false hallmarking” using metal leaves.