14 09

13 11

2018

RYUHA

Atsuo Hukuda, Shuheie Fukudu

Curated by Michal Škoda

Japanese artist Atsuo Hukuda returns to the Czech Republic after ten years with the exhibition RYUHA. This time the artist has invited his son, Shuhei Fukuda, to collaborate on a project for the Kvalitář Gallery space referencing one of the traditions of Japanese art within the context of contemporary art.

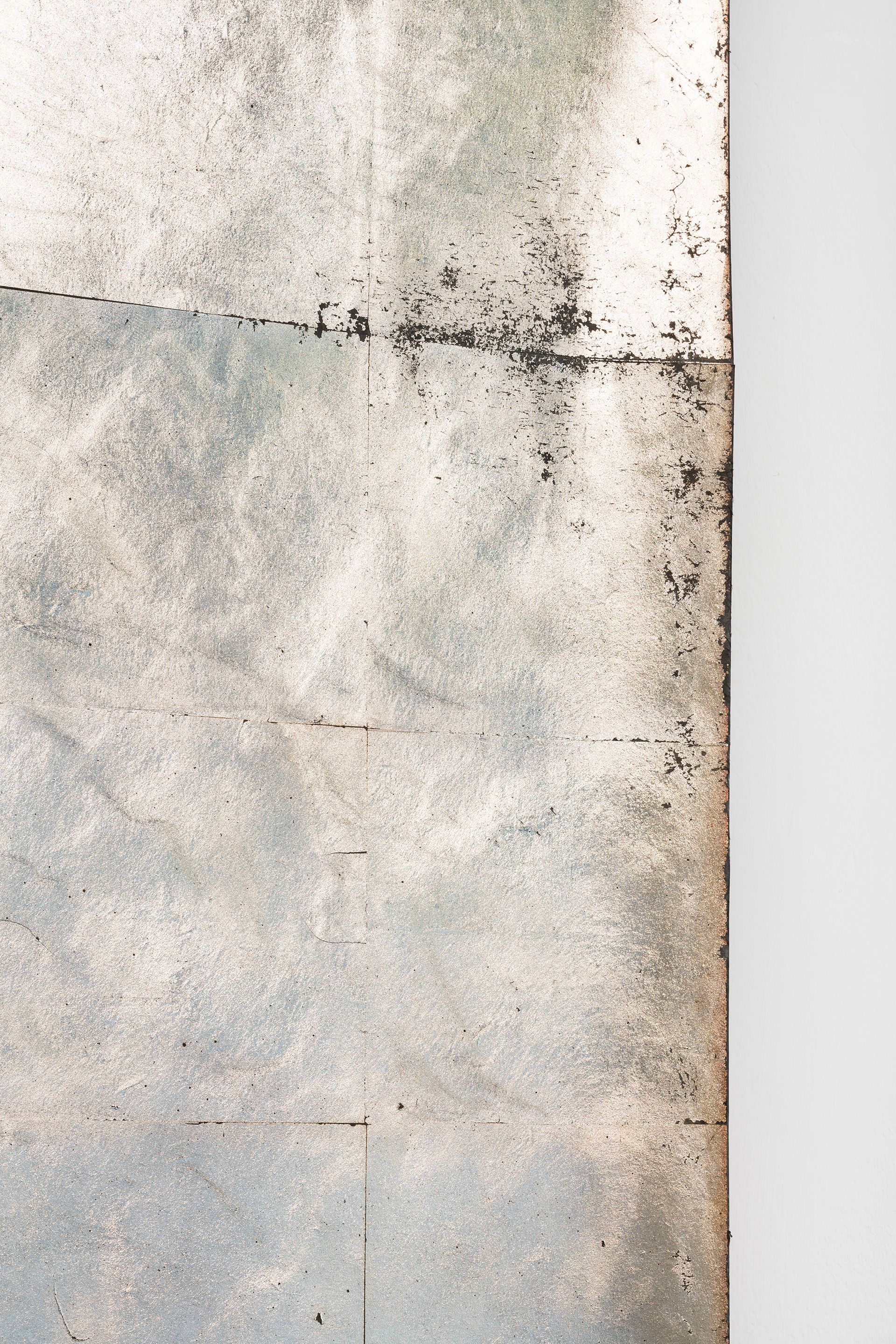

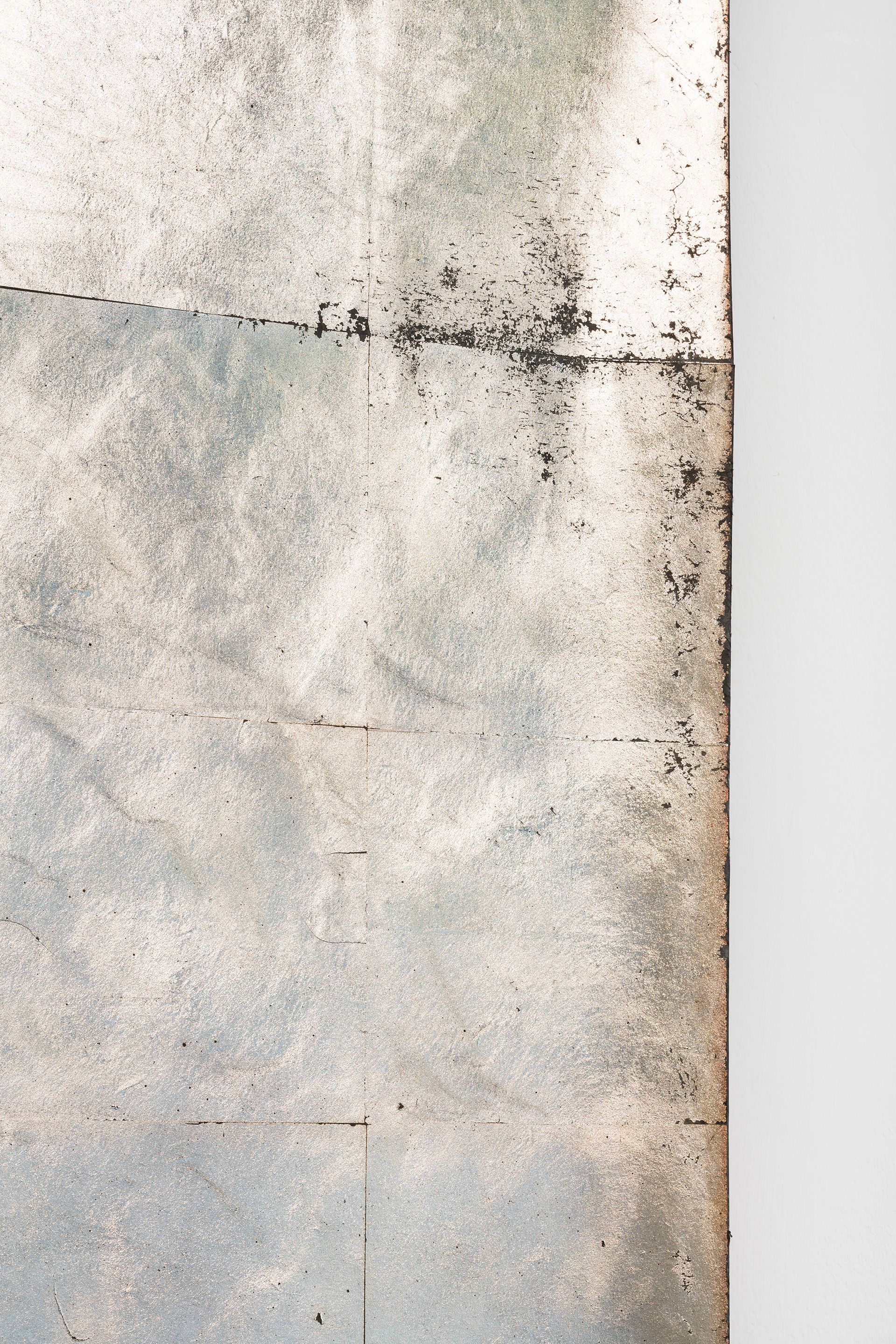

Atsuo Hukuda (1958) is an artist using traditional Japanese painting techniques and materials, such as gold/silver leaf or Urushi, a Japanese lacquer. The artist incorporates these traditional elements into his work in order to examine the identity of Japanese art following the concept “Dry/Light/Clear/Sharp.” In this way, Hukuda intervenes into a specific space with great sensitivity, creating spaces so full of silence they become endowed with a certain sacredness.

Hukuda himself notes, “The best approach for maximizing the architectonic quality of a space is to not introduce anything essential. A space and an artwork can coexist, mutually strengthening each other’s characteristics as long as the interventions remain minimal.”

Shuhei Fukuda (1997) is an art student and Hukuda’s son. He is currently studying traditional Japanese painting and examining his own approach to the world through the use of traditional techniques and materials. He is interested in variability and the relation of the material and inner world within the framework of a long-term variable process.

The fact that Hukuda has invited his son to collaborate with him is no coincidence. Alongside working on his own artistic endeavours, Hukuda is also the director of the exhibition platform Concept Space in Shibukawa. Above all, he has resided in a pedagogical role for many years. The method of teaching in Japan led him to open his own, private art school where, as opposed to traditional schools, teachers and students discuss art among themselves. Through this relationship the concept of “passing down the inheritance” of school/style/house is spread across generations, cultures, and disciplines in the broader sense. The artists, who have chosen to work with the same material, are father and son. This relationship, as one of the forms of handing down traditions and skills, in turn leads the viewer to the project’s essence.

RYUHA is a school of art in which stylised and structured skills, techniques and traditions are inherited collectively. This normally happens by bloodlines of the patriarch or through the school’s students – just as it does in the case of Ikebana, tea ceremonies, martial arts and others. In Japanese painting, Tosa-ha, Kano-ha and Rin-pa are among the most well-known Ryuha schools and styles. Koetsu Honami (1558-1637) and Sotatsu Tawaraya (date of birth and death are unknown) began working in the style known today as Rin-pa in the 17th century in Kyoto. This style was developed later in the 18th century by Korin Ogata (1658-1716) and his younger brother, Kenzan Ogata (1663-1743). This style was inherited and introduced into the Edo Period by the painter Hoitu Sakai (1761-1828), after which it was taken up by many others. The main characteristics of Rin-pa are: the use of gold/silver leaf as a background to painting, repetition of the same ornamental patterns, establishment of the painting technique known as Tarashikomi (dripping a secondary layer of paint before the first has dried), a more frequent occurrence of asymmetrical compositions rather than symmetrical, and the use of these elements on a single, flat surface – such as, for example, a background of gold/silver leaf, a graphically painted tree or ornamental pattern.

Naoko Nabon, an independent curator who has already worked on a project with both of the artists has, among other things, this to say on the topic: “Due to the fact that the Japanese were, historically speaking, an agricultural nationality living on a small island with a high likelihood of natural disasters, they always belonged to communities of various forms and sizes, such as the family, village, company, society, and nation. They also adhered to a strict hierarchical organization within each of these communities. The maintenance of “Wa,” or a harmonious relationship with the group, was the most important matter for the people and their survival.”

This however does not mean that Hukuda celebrates Japanese art, culture and tradition without doubts. Thanks to regular exhibitions abroad and interactions with colleagues from various nations, the “identity of Japanese art” has become an unavoidable point of discussion for Hukuda. This point has been properly rediscovered, examined, and developed in both objective and skeptical ways. For example, the above mentioned Rin-pa style has stood out above other schools such as the Kano-ha school. This is due to the frequent collaboration between disciplines, and the fact that the style was not passed down and developed over time though a number of bloodlines or students, but rather indirectly through followers acting out of their own free will and admiration. Hukuda also adheres to the Rin-pa lines of thinking regarding his choice of collaborators, working with various experts, such as musicians, dancers of the Japanese dance theater Butoh, cartoon storytellers and many others across different disciplines, generations, and nationalities.

Junichiro Tanizaki praised “shadows” and melancholy in a well-known essay familiar even here in the west. Shadows, to which the Japanese sense for beauty and the essence of elegance belong, create the impression of being abandoned due to the civilized light of the western world, which attempts to illuminate everything. Tanizaki however, praised subdued light as well, referencing the importance of gold leaf in Japanese spaces, which acted as a reflector in darkened places. The gold included in sliding doors and shutters not only had to capture the gentle sparkle of the room, but reflect it as well. People were therefore not only attracted to its beauty, but also its ability to provide light.

Indeed, Hukuda incorporates gold leaf according to circumstance. In order to respect the historical context, the artist notes the thinness, brightness, and brilliance of gold and creates a work that minimally intervenes into a space. Through his works, Hukuda enters a space with great sensitivity.

This method of working is also the basis for Atsua Hukuda’s and Shuhei Fukuda’s exhibition at the Kvalitář Gallery. How the exhibition communicates with the space itself is, however, something that one must decide on their own.